Variable Fault Geometry Suggests Detailed Fault‐Slip‐Rate Profiles and Geometries Are Needed for Fault‐Based Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Assessment (PSHA)

Faure Walker J.P., F. Visini, G. Roberts, C. Galasso, K. McCaffrey, Z. Mildon (2018).

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, doi: 10.1785/0120180137.

Abstract

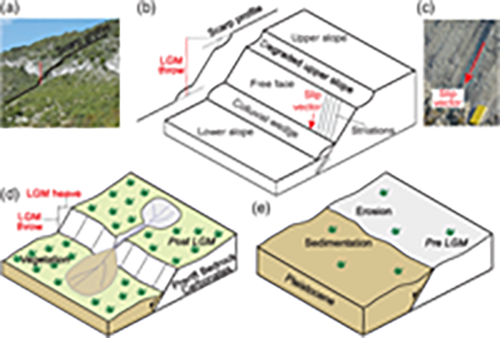

It has been suggested that a better knowledge of fault locations and slip rates improves seismic hazard assessments. However, the importance of detailed along‐fault‐slip‐rate profiles and variable fault geometry has not yet been explored. We quantify the importance for modeled seismicity rates of using multiple throw‐rate measurements to construct along‐fault throw‐rate profiles rather than basing throw‐rate profiles on a single measurement across a fault. We use data from 14 normal faults within the central Italian Apennines where we have multiple measurements along the faults. For each fault, we compared strain rates across the faults using our detailed throw‐rate profiles and degraded data and simplified profiles. We show the implied variation in average recurrence intervals for a variety of magnitudes that result. Furthermore, we demonstrate how fault geometry (variable strike and dip) can alter calculated ground‐shaking intensities at specific sites by changing the source‐to‐site distance for ground‐motion prediction equations (GMPEs). Our findings show that improved fault‐based seismic hazard calculations require detailed along‐fault throw‐rate profiles based on well‐constrained local 3D fault geometry for calculating recurrence rates and shaking intensities.

Devi effettuare l'accesso per postare un commento.