A framework for validation and benchmarking of pyroclastic current models

Esposti Ongaro T., M. Cerminara, S. J. Charbonnier, G. Lube & G. A. Valentine (2020). A framework for validation and benchmarking of pyroclastic current models.

Bulletin of Volcanology, 82/51, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-020-01388-2.

Abstract

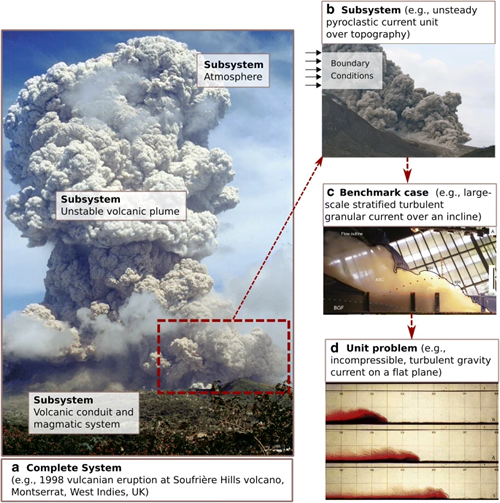

Numerical models of pyroclastic currents are widely used for fundamental research and for hazard and risk modeling that supports decision-making and crisis management. Because of their potential high impact, the credibility and adequacy of models and simulations needs to be assessed by means of an established, consensual validation process. To define a general validation framework for pyroclastic current models, we propose to follow a similar terminology and the same methodology that was put forward by Oberkampf and Trucano (Prog Aerosp Sci, 38, 2002) for the validation of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) codes designed to simulate complex engineering systems. In this framework, the term validation is distinguished from verification (i.e., the assessment of numerical solution quality), and it is used to indicate a continuous process, in which the credibility of a model with respect to its intended use(s) is progressively improved by comparisons with a suite of ad hoc experiments. The methodology is based on a hierarchical process of comparing computational solutions with experimental datasets at different levels of complexity, from unit problems (well-known, simple CFD problems), through benchmark cases (complex setups having well constrained initial and boundary conditions) and subsystems (decoupled processes at the full scale), up to the fully coupled natural system. Among validation tests, we also further distinguish between confirmation (comparison of model results with a single, well-constrained dataset) and benchmarking (inter-comparison among different models of complex experimental cases). The latter is of particular interest in volcanology, where different modeling approaches and approximations can be adopted to deal with the large epistemic uncertainty of the natural system.

Devi effettuare l'accesso per postare un commento.